- Understanding Agile Methodologies and Principles | A Complete Tutorial

- What is a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)? | Learn Overview, Steps, Benefits

- Traditional Project Management Tutorial | A Comprehensive Guide

- Total Quality Management (TQM): Complete Guide [STEP-IN]

- Total Productive Maintenance Tutorial | Get an Overview

- Virtual Team Tutorial – Learn Origin, Definition and its Scope

- The Rule of Seven in Project Management – Tutorial

- Make or Buy Decision – A Derivative Tutorial for Beginners

- What is Halo Effect? | Learn More through Tutorial

- Balanced Score Card Tutorial | Learn with Definition & Examples

- What is Supply Chain Management? | Tutorial with Examples

- Succession Planning Tutorial | A Complete Guide with Definitions

- What is Structured Brainstorming? | Quickstart & Learn the Tutorial

- Stress Management Tutorial | A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners

- What is a Statement of Work? | Learn with Definition & Examples

- What is Stakeholder Management? – The Ultimate Guide for Beginners

- How to Create a Staffing Management Plan? | Learn from Tutorial

- What is Resource Leveling? | A Comprehensive Tutorial

- Requirements Collection Tutorial: Gather Project Needs

- What Is a RACI Chart? | Learn with Example & Definitions

- Quality Assurance vs Quality Control: Tutorial with Definitions & Differences

- Project Workforce Management Tutorial | A Definitive Guide

- Project Time Management Tutorial: Strategies, Tips & Tools

- Project Management Success Criteria Tutorial | Understand and Know More

- Identify Risk Categories in Project Management | A Comprehensive Tutorial

- Project Records Management Tutorial | Quickstart -MUST READ

- Project Quality Plan (PQP) Tutorial | Ultimate Guide to Learn [BEST & NEW]

- Project Portfolio Management | A Defined Tutorial for Beginners

- Goals of a Project Manager Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Project Management Triangle Tutorial: What It Is and How to Use

- Project Management Tools Tutorial | Learn Tools & Techniques

- What is PMO (project management office)? | A Complete Tutorial from Scratch

- Project Management Lessons | Learn in 1 Day [ STEP-IN ]

- What is a Project Kickoff Meeting? | Learn Now – A Definitve Tutorial

- Project Cost Management Tutorial | Steps, Basics, and Benefits

- Types of Contracts in Project Management | Learn with Examples

- Project Activity Diagram | Ultimate Guide to Learn [BEST & NEW]

- What is Project Procurement Management? | Tutorial Explained

- Procurement Documents Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Process-Based Project Management Tutorial: A Beginner’s Guide

- What Is PRINCE2 Project Management? | A Definitive Tutorial for Beginners

- Effective Presentation Skills – Learn More through Tutorial

- Powerful Leadership Skills Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- PERT Estimation Technique Tutorial | Explained with Examples

- Pareto Chart Tool Tutorial | Learn Analysis, Diagram

- Organizational Structure Tutorial: Definition and Types

- Negotiation Skills for Project Management | Learn from the Basics

- Monte Carlo Analysis in Project Management Tutorial | A Perfect Guide to Refer

- Effective Management Styles Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Management by Objectives (MBO) Tutorial | Overview, Steps, Benefits

- Leads, Lags & Float – Understand the Difference through Tutorial

- What is Knowledge Management? – Tutorial Explained

- What is Just-in-Time Manufacturing (JIT)? | Know More through Tutorial

- Gantt Chart Tool Tutorial: The Ultimate Guide

- Extreme Project Management Tutorial – Methodology & Examples

- Introduction for Event Chain Methodology Tutorial | Guide For Beginners

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) | A Complete Tutorial for Beginners

- What Is Design of Experiments (DOE)? | Learn Now – A Definitve Tutorial

- Decision Making Tutorial – Know about Meaning, Nature, Characteristics

- Critical Path Method Tutorial | How to use CPM for project management

- What is Critical Chain Project Management? | A Complete Tutorial

- What is Conflict Management? | Learn the Definition, styles, strategies through Tutorial

- Effective Communication Skills Tutorial – Definitions and Examples

- Communication Models Tutorial – Project Management

- Methods of Communication Tutorial | A Complete Learning Path

- Communication Management Tutorial | Know more about Plans & Process

- What are Communication Channels? | Learn Now Tutorial

- Communication Blocker Tutorial | Explained with Examples

- Cause and Effect Diagrams Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- What is Benchmarking? | Technical & Competitive Tutorial

- Seven Processes of Prince2 Tutorial | Everything you Need to Know

- Design Thinking Tutorial – Quick Guide For Beginners

- What is Performance Testing | A Complete Testing Guide With Real-Time Examples Tutorial

- What is Confluence? : Tutorial For Beginners | A Complete Guide

- Lean Six Sigma Tutorial

- Agile Scrum Tutorial

- PMI-RMP Plan Risk Management Tutorial

- Designing the Blueprint Delivery Tutorial

- What is Confluence? : Tutorial For Beginners | A Complete Guide

- Program Benefits Management Tutorial

- Continuous Improvement – Agile Value Stream Mapping

- Program Organization Tutorial

- Risk and Issue Management Tutorial

- Project Integration Management Tutorial

- Planning and Control Tutorial

- Program Management Principles Tutorial

- program strategy Alignment Tutorial

- PMP Tutorial

- Program Governance Tutorial

- Program Life Cycle Management Tutorial

- PMP Exam Preparation Tutorial

- PMI-PgMP Tutorial

- Agile Methodologies and Frameworks- Kanban and Lean Management Tutorial

- JIRA Tutorial

- Primavera P6 Tutorial

- Understanding Agile Methodologies and Principles | A Complete Tutorial

- What is a Work Breakdown Structure (WBS)? | Learn Overview, Steps, Benefits

- Traditional Project Management Tutorial | A Comprehensive Guide

- Total Quality Management (TQM): Complete Guide [STEP-IN]

- Total Productive Maintenance Tutorial | Get an Overview

- Virtual Team Tutorial – Learn Origin, Definition and its Scope

- The Rule of Seven in Project Management – Tutorial

- Make or Buy Decision – A Derivative Tutorial for Beginners

- What is Halo Effect? | Learn More through Tutorial

- Balanced Score Card Tutorial | Learn with Definition & Examples

- What is Supply Chain Management? | Tutorial with Examples

- Succession Planning Tutorial | A Complete Guide with Definitions

- What is Structured Brainstorming? | Quickstart & Learn the Tutorial

- Stress Management Tutorial | A Comprehensive Guide for Beginners

- What is a Statement of Work? | Learn with Definition & Examples

- What is Stakeholder Management? – The Ultimate Guide for Beginners

- How to Create a Staffing Management Plan? | Learn from Tutorial

- What is Resource Leveling? | A Comprehensive Tutorial

- Requirements Collection Tutorial: Gather Project Needs

- What Is a RACI Chart? | Learn with Example & Definitions

- Quality Assurance vs Quality Control: Tutorial with Definitions & Differences

- Project Workforce Management Tutorial | A Definitive Guide

- Project Time Management Tutorial: Strategies, Tips & Tools

- Project Management Success Criteria Tutorial | Understand and Know More

- Identify Risk Categories in Project Management | A Comprehensive Tutorial

- Project Records Management Tutorial | Quickstart -MUST READ

- Project Quality Plan (PQP) Tutorial | Ultimate Guide to Learn [BEST & NEW]

- Project Portfolio Management | A Defined Tutorial for Beginners

- Goals of a Project Manager Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Project Management Triangle Tutorial: What It Is and How to Use

- Project Management Tools Tutorial | Learn Tools & Techniques

- What is PMO (project management office)? | A Complete Tutorial from Scratch

- Project Management Lessons | Learn in 1 Day [ STEP-IN ]

- What is a Project Kickoff Meeting? | Learn Now – A Definitve Tutorial

- Project Cost Management Tutorial | Steps, Basics, and Benefits

- Types of Contracts in Project Management | Learn with Examples

- Project Activity Diagram | Ultimate Guide to Learn [BEST & NEW]

- What is Project Procurement Management? | Tutorial Explained

- Procurement Documents Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Process-Based Project Management Tutorial: A Beginner’s Guide

- What Is PRINCE2 Project Management? | A Definitive Tutorial for Beginners

- Effective Presentation Skills – Learn More through Tutorial

- Powerful Leadership Skills Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- PERT Estimation Technique Tutorial | Explained with Examples

- Pareto Chart Tool Tutorial | Learn Analysis, Diagram

- Organizational Structure Tutorial: Definition and Types

- Negotiation Skills for Project Management | Learn from the Basics

- Monte Carlo Analysis in Project Management Tutorial | A Perfect Guide to Refer

- Effective Management Styles Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- Management by Objectives (MBO) Tutorial | Overview, Steps, Benefits

- Leads, Lags & Float – Understand the Difference through Tutorial

- What is Knowledge Management? – Tutorial Explained

- What is Just-in-Time Manufacturing (JIT)? | Know More through Tutorial

- Gantt Chart Tool Tutorial: The Ultimate Guide

- Extreme Project Management Tutorial – Methodology & Examples

- Introduction for Event Chain Methodology Tutorial | Guide For Beginners

- Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) | A Complete Tutorial for Beginners

- What Is Design of Experiments (DOE)? | Learn Now – A Definitve Tutorial

- Decision Making Tutorial – Know about Meaning, Nature, Characteristics

- Critical Path Method Tutorial | How to use CPM for project management

- What is Critical Chain Project Management? | A Complete Tutorial

- What is Conflict Management? | Learn the Definition, styles, strategies through Tutorial

- Effective Communication Skills Tutorial – Definitions and Examples

- Communication Models Tutorial – Project Management

- Methods of Communication Tutorial | A Complete Learning Path

- Communication Management Tutorial | Know more about Plans & Process

- What are Communication Channels? | Learn Now Tutorial

- Communication Blocker Tutorial | Explained with Examples

- Cause and Effect Diagrams Tutorial | The Ultimate Guide

- What is Benchmarking? | Technical & Competitive Tutorial

- Seven Processes of Prince2 Tutorial | Everything you Need to Know

- Design Thinking Tutorial – Quick Guide For Beginners

- What is Performance Testing | A Complete Testing Guide With Real-Time Examples Tutorial

- What is Confluence? : Tutorial For Beginners | A Complete Guide

- Lean Six Sigma Tutorial

- Agile Scrum Tutorial

- PMI-RMP Plan Risk Management Tutorial

- Designing the Blueprint Delivery Tutorial

- What is Confluence? : Tutorial For Beginners | A Complete Guide

- Program Benefits Management Tutorial

- Continuous Improvement – Agile Value Stream Mapping

- Program Organization Tutorial

- Risk and Issue Management Tutorial

- Project Integration Management Tutorial

- Planning and Control Tutorial

- Program Management Principles Tutorial

- program strategy Alignment Tutorial

- PMP Tutorial

- Program Governance Tutorial

- Program Life Cycle Management Tutorial

- PMP Exam Preparation Tutorial

- PMI-PgMP Tutorial

- Agile Methodologies and Frameworks- Kanban and Lean Management Tutorial

- JIRA Tutorial

- Primavera P6 Tutorial

Program Governance Tutorial

Last updated on 29th Sep 2020, Blog, Project Management, Tutorials

What is Program Governance?

José begins exploring what will have to be different about governance of this program versus his prior project assignments.

Program governance, he discovers, is the overall framework for execution of a corporate program. It establishes processes and a structure for communication, implementation, monitoring, and ensuring that policies and best practices are followed. In other words, oversight and control ensure that the program’s goals and objectives are aligned with those of the overall enterprise.

A governance framework needs to be repeatable and able to be used across an organization and at different points in time. The framework also needs to account for tangible assets such as money and technology as well as intangible ones like employees and customers.

Successful program governance, José learns, will provide a variety of benefits to his organization. It will:

- increase efficiency and help reduce risk.

- provide a framework for managing issues, opportunities, risks, complexity, and competing priorities.

- help to focus resources across an organization to meet strategic business goals.

Program

A program is a major enterprise initiative — an element in the overall business strategy and direction. Here’s a formal definition:

A collection of projects with a common goal or success “vision” under integrated management. These projects consist of people, technology, and processes aimed at implementing significant business and technology change.

Governance

As programs progress, they require a linkage mechanism that ensures alignment between business strategy and direction, and the path to needed outcomes over the life of the program. In other words, this mechanism must help the program sustain its potential to deliver its promised value. Moreover, other mechanisms must provide oversight and control during program execution. They must help managers assess the program’s current state and adjust content and direction if necessary. They should also allow management to refine the definition of success to maintain alignment with evolving business strategy.

Subscribe For Free Demo

Error: Contact form not found.

The simple diagram in Figure 1 provides a view of the overall context in which programs are enabled and executed.

Overall work context for programs

As the simple diagram shows, the overall business and IT strategy and direction are first defined for the enterprise. Next, some enterprises create portfolios of programs and projects as part of the execution mechanism for business and IT strategies / direction. Therefore, we can think of programs as elements — among others — that an enterprise enables to execute its business and IT strategies / direction.

To achieve the necessary linkage, oversight, and control we described above, programs must institute effective governance, which for program management is defined as follows:

Governance, for a program, is a combination of individuals filling executive and management roles, program oversight functions organized into structures, and policies that define management principles and decision making.

This combination is focused upon providing direction and oversight, which guide the achievement of the needed business outcome from the execution of the program effort, and providing data and feedback, which measure the ongoing contribution by the program to needed results within the overall business strategy and direction.

The concept of governance has multiple dimensions: people, roles, structures, and policies. Overseeing and actively managing program work is a more complex undertaking than project management. Furthermore, programs are dynamic, not static. They must respond to external events and changing conditions. Therefore, an effective governance structure and set of governance functions must provide the means to identify, assess, and respond to internal and external events and changes by adjusting program components or features. A poor (or nonexistent) governance structure will leave the program in a continuously reactive state, constantly struggling to catch up with changing conditions.

The Governance Team

By understanding the goals, scope, and benefits of program governance, and the goals of the program for which he is responsible, José is now in a position to design an approach to governance for his program.

The first step is determining the stakeholders who will be part of it all. Every company has its own stakeholder groups, and the key stakeholder representatives with a direct connection to the program will need to be part of the governance structure.

For TechAll, the company’s CEO, CFO, and CIO all may have important roles to play at different stages in the program too. If supplier contracts are involved, the company’s chief legal officer may have a role, as well as the managers of the specific product lines involved.

Deploy with confidence

Consistently deliver high-quality software faster using DevOps services on IBM Bluemix. Sign up for a free Bluemix cloud trial, and get started.

In this article we will take up a number of elements in governance, including:

- Organizational structures: These may include a program steering committee, a Program Management Office (PMO), the program organizational model, and the project organizational model.

- Roles: These may include the executive sponsor(s), a steering committee member, the program director / manager, the PMO manager, and project managers.

- Mechanisms: Designed to provide guidance and direction, these may include policies, governance principles, and decision or authority specifications.

Goals of program governance

Program governance addresses a number of goals:

- Define and implement a structure within which to execute program management and administration

- Provide active direction, periodically review interim results, and identify and execute adjustments to ensure achievement of the planned outcome (which contributes to success of the overall business strategy)

To achieve these goals, organizations define, agree upon, and implement structures within the program effort. There is no single “best” structure; rather, the structure should “fit” the enterprise’s organizational dynamics and practices. For example, within a consensus-oriented business culture, the program structure should provide for achieving, and continuously refining, consensus around major program outcomes. A program organizational structure that runs counter to components of the business culture will struggle to achieve momentum and forward motion.

Active direction for the program is achieved through a combination of the right individuals, an effective structure for management and oversight, and a “set” of program roles and responsibilities. Roles and responsibilities should be defined and structured, with the needed outcomes of the program in mind, and to “fit” within the management philosophy and enterprise approach.

Program governance structure and roles

To be effective, the individuals who direct the program and those who oversee its work activities must be organized, and their contributions must be modeled to ensure that authority and decision-making has a clear source, the work of management and oversight is efficient, and the needs for direction and decisions are all addressed.

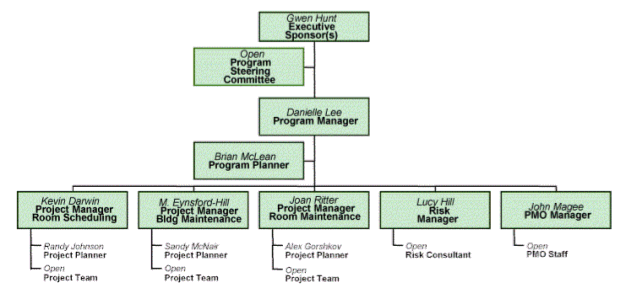

An organizational model should decompose all management and oversight functions, and describe the relationships among them. Figure 2 is a fairly typical model; and variations are possible.

Sample program governance structure

Below, we will look at three roles show in the figure

- Executive sponsor(s)

- Steering committee

- Program director / manager

Executive sponsor(s): Direction and oversight

A program needs one or more executive sponsors to ensure that it will make an appropriate and necessary contribution to the overall enterprise business strategy.

Typically, this executive (Gwen Hunt, in our example) “owns” the major business segment that will be both the program’s principal beneficiary and accountable for achieving the program’s defined outcome(s) specified in the overall business strategy. For a major initiative that will impact and benefit multiple enterprise segments, multiple executives typically share this accountability. This might be structured in one of two ways:

- Multiple executive sponsors share responsibility for the program’s success and achievement of defined outcomes.

- One senior executive sponsor is designated as the final decision maker, and other executive sponsors serve as members of a steering committee. In addition to providing advice and impact assessments, these committee members are jointly responsible — with the senior executive sponsor — for a successful program outcome as well as desired outcomes in their respective business segments.

Steering committee: Directing / advising

Large initiatives typically impact more than one business segment, and multiple segments often own different (but dependent or integrated) outcomes and results within the context of the overall business strategy and direction.

Such initiatives require a governance mechanism through which all segment representatives can reach agreement on a direction that will result in desired outcomes for everyone. These programs also need a forum in which the representatives can raise issues and adjust direction, resources, or timing by consensus, as required. This mechanism is often a steering committee.

Steering committees can follow different models. For example, a committee might consist of:

- Executive-level sponsors who must reach consensus on issues, changes, and adjustments in order to proceed (consensus model)

- Executives and senior managers who are stakeholders for some aspect of the defined outcomes. Their role is to understand issues and needed changes, provide advice and assessment of potential impact, and make needed adjustments within their own responsibility area (consultative model)

- Representatives for the major business segments who are responsible for outcomes, or portions of outcomes, within the business strategy and direction. Their role is to monitor program progress, understand issues raised and adjustments made, assess potential impact within their own business segments, and carry back information about committee decisions to their respective business segments (advisory model)

Consultative and advisory models have a number of similarities. A key difference, however, is that in a consultative model, each business segment has significant ownership of the work effort and its results within that segment. In the advisory model, that ownership is diminished. Information is carried back to the business segment, and any decisions, adjustments, and issue resolutions are expected to conform to the direction provided by the program governance body or structure.

The program director / manager: Management and integration

It would be simple — and wrong — to assume that a program director / manager (to keep it simple, let’s use program manager) has nearly the same functions and responsibilities as those of a classic project manager.

A program, as we know, consists of multiple projects, each with its own project manager. Does this, then, make the program manager a “super project manager?” Table 1 compares the two roles.

| Program manager | Project manager |

|---|---|

| Integrates efforts, continuously assesses and refines approaches and plans, ensures good communication. | Plans, organizes, directs, and controls the project effort. |

| Directs managers to achieve defined outcomes aligned with business strategy. | Manages for on-time delivery of specific products. |

| Acts as the implementation arm of the program sponsor(s) and / or steering committee. | Manages work within the project plan framework. |

| Manages managers. | Manages technical staff. |

As Table shows, the program manager and project manager roles are quite different from one another. Whereas project managers typically focus on delivering a specific component, program managers typically focus on one or more outcomes that are business strategy components.

Maintaining links to business strategy

Throughout program planning and execution, managers must ensure that the program sustains a connection to the business strategy. As we have noted, this strategy is dynamic, not static. Both internal and external events affect the enterprise’s initiatives, so programs need mechanisms that will maintain a link between the initiative and the business strategy, and provide for effective data exchange and necessary adjustments.

We can divide such mechanisms into two categories: those active during mobilization and planning, and those active during execution.

Mobilization strategic review

A number of work products specifically related to an individual program effort should be developed, and agreed upon, during the definition of the business strategy. These products describe the results of strategic work efforts to define the program, and justify proceeding with it. They provide initial links to the business strategy and help to frame the mobilization effort. These products should include:

- IT goals and strategy

- Program capital and expenses budget

- Program benefits definition

- Program outline

- Candidate projects identification

- Program mobilization plan

- Consulting and staffing agreements

A business strategy review should be part of the overall mobilization process for both the program and its constituent projects, to check the quality of the business strategy input and to determine readiness to proceed.

Planning strategic review

Both the overall planning process for the program and the planning process for its constituent projects should require a review of the current “state” of the program business strategy. This will ensure that the input for plans and schedules includes the business strategy elements in their most current form.

Program execution strategy reviews

As the program proceeds, the program plan and schedule should provide for periodic strategy reviews by the program sponsor(s) and / or steering committee.

The schedule for these reviews can be aligned with the program’s phase structure, which cuts across all of the constituent projects. As a phase-end approaches, reviewers can compare the program’s current state and results against the then-current business strategy, and propose needed adjustments.

Decisions and authority

An important aspect of program governance is assigning specific decision-making authority to each executive and management role. Program managers can hold special group work sessions for this purpose and then create and distribute a matrix for major decision areas and roles. Figure 3 shows a sample decision authority matrix that has proven useful in past program efforts:

Sample program decision rights by role matrix

In Figure, the “decision qualifiers” indicate the scope of the role’s decision-making powers. These qualifiers should be as specific as possible, preferably using some metric to indicate the role’s upper limit in a decision situation.

A simple mechanism like this, posted on the program intranet site, will be a good starting point for team members who require a decision or need authorization to proceed with some action.

Getting organized

From an organizational perspective, a program is not a single structure, but rather a set of integrated (and interacting) structures. There is no “best” way to organize program resources into a set of structures, but we can look at typical organizational components and their functions, and comment on their value.

The components we will examine in this portion of the article are:

- The program “core” organization

- The Program Management Office (PMO)

- Organization of constituent program projects

The program core organization

An organizational structure is required to support and enable all of the program’s day-to-day oversight and integration efforts. At the heart of this structure is the program manager, whose role we have already discussed. The program manager will typically be supported by Program Management Office (PMO) staff, but will likely have a small group of individuals who either report directly to him / her or are identified as part of the PMO staff, but work for him / her.

These individuals help the program manager to identify and understand departures from plan in terms of progress and expenditures, and to coordinate communications.

Table 2 describes possible roles for these core staff members.

| Role name | Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Program planner | A management role, responsible for construction and maintenance of all planning strategies, plans, and schedules for the program and constituent projects. |

| Budget administrator | A PMO role that administers and reports all program finances; the budget administrator also serves as a liaison to internal financial management, which supplies controls and interprets corporate financial policy for the program. |

| Communications coordinator | A PMO role that coordinates and disseminates all program information to both program staff and the broader enterprise. This person also serves as a liaison to corporate communications, which interprets communication policies and handles external communication for the program. |

This role list is not exhaustive; some programs define a significant number of other staff and management roles for their core organization. To some degree, the roles you select should reflect specific program needs and the program manager’s style, as the following example illustrates.

The program planner role

The program planner is responsible for all planning within the program. This is a management role that addresses the development of planning strategies and approaches, the definition and fulfillment of other planning roles, and the development of work plans for the program, its constituent projects, and other parallel efforts, such as quality assurance and testing.

A number of roles report to the program planner, including a planner for each project that may vary from a full-time to a one-third full-time-equivalent (FTE) commitment, depending upon the program’s planning stage.

A program estimator may also report to the program planner. This individual is responsible for sizing the work effort and estimating resource requirements.

In addition, certain other staff roles will have a matrix reporting relationship to the program planner in order to construct and validate work approaches, plans, and estimates. For example, the manager responsible for testing code assets has a matrix reporting relationship to the program planner for developing test strategies, plans, and estimates, and then integrating these into the overall program plan.

A Program Management Office model

The Program Management Office (PMO) provides support along administrative, financial, process, and staff dimensions associated with successful program execution. The PMO’s administrative support includes plan conformance tracking, management of work products, resources administration, and physical and technical environment support.

The PMO also provides review and tracking of financial expenditures, generation of required reports and financial documents, and liaison with the enterprise financial organization to ensure compliance with policies and practices.

Finally, the PMO provides and administers policies, procedures, and practices that provide an operational framework for program staff. This encompasses issues such as time reporting, contracting for outside resources, allowable expenses, training, communications about the program, and internal reporting practices.

Figure shows one possible organizational model for a Program Management Office (PMO).

Example Program Management Office organization

The roles shown in Figure are fairly typical for a large program effort. Depending upon the program execution stage, some roles may become either more or less active. In this model, in at least one instance the same person fills two roles: status and tracking as well as issues management.

Also, in some enterprises, a role may be delegated to an individual working within an existing function to provide program support. For example, many enterprises have a function that will deal with outside consulting and contracting firms to obtain external staff resources. An individual from that function can fill a role in the PMO, while being assigned part-time to the program.

Also notice that some of the roles we identified above as part of the program “core” organization are shown here: program planner, communications coordinator, and budget administrator. In this instance, for administrative and resource approval purposes, these roles report to the PMO manager.

Project structure within a program model

The organization structure for individual projects within a program effort is usually straightforward: The program organization — most typically the PMO — simply supplies administrative support and technical resources for such concerns as facilities, training, budget, and so forth.

Figure 5 shows a sample organizational structure for a project within a program.

Sample organizational structure for a project within a program

For the most part, projects within a program effort can be thought of as primarily delivery organizations. These projects are organized and function to deliver elements that will be integrated together into a larger whole — in software projects, for example — that would be code assets. However, a program may also have projects and teams with different purposes and/or structures. For example, a team might focus solely upon product testing, quality assurance, or systems architecture. These special-purpose teams may also provide services to multiple projects or be responsible for work conducted in parallel to program delivery efforts.

Key Success Factors of Governance Organizations that are successful at governance exhibit behaviors reflective of the basic facets of governance (accountability, authority, and decision-making). However, successful governance organizations also exemplify additional behaviors that normalize and strengthen their contributions to the organization overall. Successful governance makes use of cross-functional teams that include members with a broad range of experiences and skill sets. This provides the organization with new ways of viewing circumstances, varied approaches to problem solving, and creative solutions. It also gives key participants a way to engage in the governance process. While authority and accountability may depend on hierarchy within the organization, important stakeholders – not just those serving on governance boards, committees, or program offices – should feel they are a part of the governance process. Ownership should span the organization with extensive opportunities for feedback. The administrative team, executive leaders, and other authority figures should be available and receptive. Governance frameworks that depend entirely on overworked, unavailable executive managers will only lead to failure. Successful governance frameworks usually include a tiered approach that outlines decision-making thresholds and a detailed escalation process that should be undertaken when the need arises or as prescribed in policies. This approach empowers middle managers to make timely decisions without waiting for executive-level quorums. Knowledge management is also a key component of successful governance. Access to documentation that provides a clear explanation of the governance structure and its procedures should be available to all participants. Deviation from the governance norm should not occur unless a formal change to policies has taken place. Lastly, governance is most successful within organizations that exhibit a cooperative approach to its adoption. Cultivating a spirit of organizational ownership and exhibiting the will to triumph despite the inevitable hiccups that occur during the early implementation phase can lead to successful governance outcomes

Why project governance is critical to project success

Establishing project governance is not as easy as it sounds. Considerable investment needs to be made while getting on a new project. What’s even more challenging is to quantify what benefits are associated with it. Given below are four key benefits of project governance:

- Single point of accountability

- Issue management and resolution

- Information distribution and clear communication

- Outlines roles, relationships, and responsibility among project stakeholders

Lack of proper foundation of project governance can derail even a well-devised project. While it is imperative to incorporate excellent technical insights and innovative ideas into the project, one cannot undermine the significance of good project management and governance. It helps you to put up questions and issues that were not even visible before its implementation. It is a multiple-in-one tool for project management which gives a new dimension and a touch of distinct quality to an otherwise ordinary project.

How to Build a Strong Governance Model

There has been a recent emphasis in the corporate world on best practices for corporate governance. The increased focus on governance has many boards of directors looking for ways to enhance their governance practices. Many of them are committed enough to the governance process that they’re allocating financial resources to improving governance practices within their companies.

Boards that focus on governance are starting by re-evaluating their policies, establishing board-level risk committees and clarifying the goals of all their committees. One of the newer strategies of boards is to appoint a Chief Risk Officer (CRO), and the preference is for the CRO to be an independent director.

For many boards, it’s back to square one with comparing their current governance model with how it functions in today’s marketplace, finding gaps and working toward optimizing it.

What Is a Governance Model?

Deloitte’s guide to governance models, “Developing an Effective Governance Operating Model,” outlines in detail how to build and improve governance models.

Every company has unique circumstances and needs, and their governance models will reflect the uniqueness of their companies. There are four major components of a governance model, and each has important key subcomponents:

- 1. StructureThe subcomponents under structure are organizational design and reporting structure and the structure of the committees and charters.

- 2. Oversight Responsibilities Key subcomponents under this component are board oversight and responsibilities, management accountability and authority, and the authority and responsibilities of the committees.

- 3. Talent and Culture Subcomponents under this section are performance management and incentives, business and operating principles, and leadership development and talent programs.

- 4. Infrastructure Policies and procedures, reporting and communication, and technology are the key subcomponents under this section.

Turning the Framework Into an Operating Model

Deloitte developed their Governance Framework as a tool to help corporations review and improve their governance frameworks. The governance processes they developed highlight the various elements of governance, clarify roles, and explain the relationships between governance, risk management and organizational culture.

The infrastructure surrounds all elements of Deloitte’s governance framework. The infrastructure includes the people, processes and systems that management puts in place every day. The infrastructure includes communication processes to transfer information to the board, stakeholders and management.

In addition to overseeing the company’s governance processes, boards need to play a role in developing parts of the operating model and participating in activities. The board’s role in development should focus on governance issues such as strategy, integrity, talent, performance and risk governance. Thus, the governance framework and operating model is a process for turning the framework components into policies and protocols.

What Are the Components of a Governance Operating Model?

The main components of a governance model contain some important key aspects:

Board Oversight and Responsibilities

The governance model offers boards a way to articulate the oversight process, engage management in communication about governance matters, and learn where governance activities occur at various junctures in the company.

Committee Authorities and Responsibilities

Much of boards’ work happens in committees. The governance model helps define the work and authority of its committees and outlines how committees communicate and report their efforts to the board and management team.

Organizational Design and Reporting Structure

Governance models should establish the authority that presides over compliance, risk, legal, finance and audit matters. The model should also define how the board will oversee risks across all regions and businesses. The organizational design and reporting structure should be made clear to employees and stakeholders.

Management Accountability and Authority

The governance model should specify authority and accountability for key roles and identify a governance process for managing disagreements. Governance models should bring balance and improved communication between those making decisions about risks and risk managers. The model should also ensure that individuals know the rights and limits associated with their decisions. Boards should acknowledge the control functions at the regional and global levels.

Performance Management and Incentives

Incentives can enhance performance, but boards need to assess when incentives interfere with preserving assets and taking risks. A governance model should establish goals for performance, with the goal of getting the best value while considering risks and preserving assets. The goals should reflect the corporate tone and culture.

Three-Part Approach to Enhancing or Establishing a Governance Operating Model

Deloitte recommends a three-part approach to establishing a new governance operating model or enhancing an existing model. They’re not suggesting that the board take responsibility for every part of the governance model. What they are suggesting is that boards are uniquely positioned to form the governance model and to delegate duties to the appropriate parties to carry it out. The three parts are as follows:

Part I

Define the operating requirements for your governance model. Look for frameworks that will work best for your organization or design your own. Factor in any applicable regulatory, governance or legal requirements. Consider the scope of your operations and how governance factors in all aspects of it. Understand your current state of governance, including its strengths and weaknesses.

Part II

Design the governance operating model and its components. Define the key accountabilities, decision rights, and path for escalating matters up the levels of authority.

Part III

The final part is implementing the governance operating model. The completed model should define how boards will measure their success using standards and metrics. The model should tie governance requirements, organizational functions and business requirements together and allocate resources accordingly. Implementation should include a schedule of how often the board reviews the governance operating model and may suggest that a third party participate in reviewing the plan. The review process should include the components, the plan and the implementation.

Concluding Thoughts About Building Strong Governance Models

With so much at stake and so much to oversee, boards need the assistance of electronic board management systems to help them address the issue of improving governance practices. Diligent Boards and the integrated suite of governance tools in Governance Cloud is the perfect solution for boards working on their governance models. Governance Cloud boasts high-level security in each of its programs, including the board portal, secure messaging, minutes program, board evaluations, D&O questionnaires and entity management software programs. Having a fully integrated Enterprise Governance Management system will aid board directors in developing governance frameworks that work for the benefit of the board, the managers, shareholders and stakeholders.

Conclusion

Establishing a governance framework is one of the most significant efforts required for program mobilization. The success of this effort has a direct correlation with the program’s potential for long-term success because governance enables the program work, addressing such needs as:

- Continuous linkage to enterprise business strategy and direction

- Clear and well-understood decision-making authority

- Effective oversight of (and insight into) program progress and direction, including the capability to identify and execute necessary adjustments in the face of internal / external events and changes

- Executive control over program evolution and outcomes